|

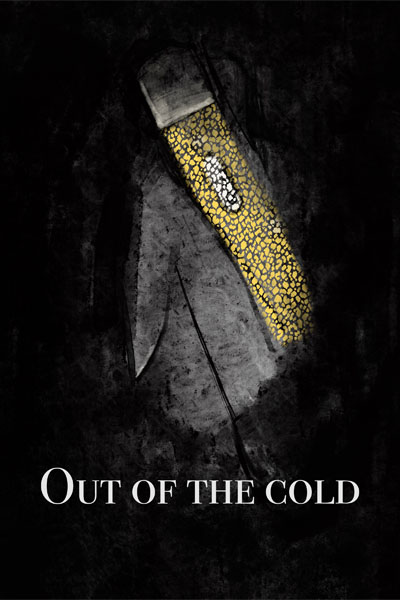

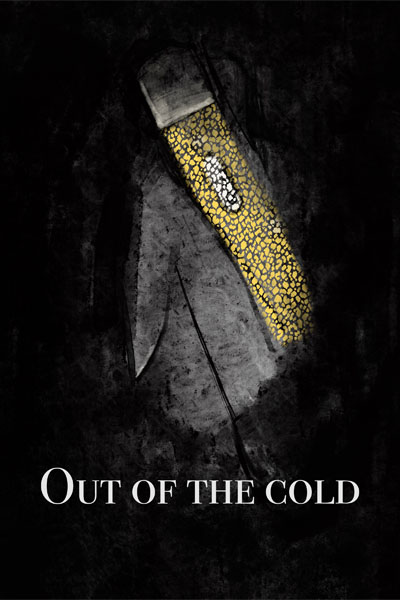

The rain fell on him as he died and kept on well after he was dead. A Thursday evening in early July, probably late, almost dark. Five pieces of a pocket knife in his right front pants pocket. Corduroy. The breast pocket of his heavy wool coat held a damp bi-fold wallet. Inside it an expired driver's license, social security card, Army ID, VA card, Medicare Card, two Kroger's Shoppers Cards, three twenty-dollar bills, and, in one of four plastic photo sleeves, two pictures stuck back-to-back. The other sleeves empty. A picture of him, me, and my little brother Timothy standing in a Mississippi state park with an Indian name, something with a mingo or an oochie at the end. I remember that. Timothy (always Timothy, never Timmy) butchered the pronunciation as we wandered the park at his side. We giggled every time he did in that pure, unburdened way only prepubescent kids can. He would look down on us, bemused. We were kids, ten and six. 1972. He was in his forties. The photo was barely recognizable. Time and those drenching hours had done damage, but I remembered it. He asked a big man standing near us to take our picture with my Kodak 110 Instamatic. The man, sweating in the delta sun, looking around vacantly as if he had lost his family, agreed. We clung next to him, tight to his hips like appendages, his arms draped our bony shoulders, cigarette dangling from his lip like a southern Humphrey Bogart as the big man pushed the little red button. We squinted into the Mississippi sun, the big man's shadow stretched out in front of us like an oil spill threatening our feet. Some things stick, a ring on a coffee table. That day stuck. Hot, but idyllic. The kind only a child can have, brought through time, now stuck to the top of the scratched plastic sleeve, colors bleeding. From the hundreds taken off that camera, that one made the wallet. I'll never know why. I had stacks of them from those four consecutive summers my mom called "summer with your father." They divorced in '68 when Timothy and I were six and two. I put them in one shoe box after another, planning to put them in an album someday. Somedays aren't guaranteed. The little silver and black square box churned out poorly colored, grainy images from another world, one revolving around a different, brighter, warmer sun. He cut that park picture down to fit in that plastic sleeve - cutting out the big man's shadow on the bottom, the blue sky on top, a trail sign on the right, a wooden bench on the left. The trimming left the three of us centered on a wide concrete walk lined by explosions of pink and red azaleas, marching to periodic magnolia trees meandering, then disappearing into a sea of pines. It could have been anywhere only sunshine and smiles were allowed. Maybe that's why he chose it. The other picture was older. Black and white with scalloped edges. I had never seen it. Its left half ruined by color bleed and water damage. The visible half revealed a short sleeve and elbow, part of a leg and foot, someone standing in a yard somewhere. In the background of the lower right corner, a structure, rough wooden planks, maybe a barn. I put them and the wallet into a hinged leather box to hold what was left of him. Army medals and badges, cheap rings, a wedding band, a chrome 32 caliber handgun, a service picture of him in full dress - Sergeant First Class. Occasionally I go through it again. The wallet and those two photos last, the last things to feel his heartbeat. That second picture always a mystery. I put those three twenties in his wallet the day before, Wednesday, almost fifty years since oochie park. We sat at the small round table in the kitchen nook of a 1930s double brick built by his second wife's first husband. He sat in the corner chair, surrounded by multi-paned windows. The early summer day glowed outside as he inspected pocket knife parts laying on a plastic placemat with giant sunflowers. "Need to fix it. Dropped it. Came apart. Need to fix it." He said. A yellow Schrade. I found out later it was a 720T Old Timer. Not just a pocket knife, but a jack blade. Two blades. One big, one small. He always carried one and collected them. I never asked why. Going through his things, I found a large boot box, Justin brand, in the back corner of his closet, bulging with varied colors of rectangles of steel, bone, and plastic. One edge of the box repaired with a piece of silver duct tape. I counted one-hundred and thirty-two: Case, Old Timer, Schrade, Barlow, Rough Rider, Uncle Henry. I remembered the box. Always high on a closet shelf when Timothy and I were around for those summers. I'm sure there was a story about some of them - maybe all of them - if I had asked. Never did, so I'll never know. A major life regret. He studied the knife parts like a jeweler, squinting behind glasses resting halfway down his nose. He looked confused, as if the few parts had turned to a thousand before his eyes. At ninety, his cognition had begun accelerating way faster with each passing minute like the expanding universe. I noticed it with every visit. Ethereal pieces of him, stretching away like dandelion seeds in the cosmic breeze. Only certain things from the past were tied down. I'd been through that before. Before my grandmother on my mom's side passed away at ninety-eight, she told me an elaborate, very specific story about taking a train ride to New Orleans on the L&N Railroad as a teenager. Went to see Aunt Rebecca and that crazy Mardi Gras, she said. She remembered what she wore, the cost of the ticket, the rail car number, and how long it took. She then called me Gilbert - her first son who never made it off Iwo Jima - grabbed my wrist and pleaded with me not to enlist because Gilly you are not made for that nasty business, and so many boys are dying over there. Very old women have a much stronger grip than you might imagine. He could fix things. Most anything but his first marriage. Appliances, cars, watches, grandfather clocks. When I was thirteen, during the last of the Summers with your Father, he told me a story about Korea while Timothy napped on the couch in one of his countless rented trailers, the ones affordable on an Army pension and odd jobs. Second Indian Head Division, 23rd Regiment, K Company. He handed me a Dr. Pepper from the fridge and poured himself a cup of coffee. We sat at a folded-leg card table that served as the kitchen table. It had rained all day and was unusually cold for a Kentucky summer. "It's cold and raining," I said, looking out the small window above the table. "I wanted to play outside." "Yep. Sorry son. You want to hear a story about real cold?" I turned back to him from watching water pelt a blue and red plastic fire truck Timothy had left in the yard. "While I was in Korea. Track came off the Sherman." He said. "What's a Sherman?" I said. "A tank. You know that. I've told you that before." I nodded, he continued. "Minus thirty degrees. Cold. Ice crystals appeared like lightning bugs in front of your face, just breathing. Our track wrench broke in half like a dry stick. Son-of-Buck named Carl Tilden pulled on the end of it, and I pushed. It snapped. We tumbled off the side of the road into hard-packed snow like a sack of potatoes. Rest of crew laughing. Carl and I weren't, then we joined in. Hard not to. Felt good to hear some guys laughing. Not a lot of that going on over there." "That sounds funny." I said. "It was until we started to scramble up." He said. "What do you mean?" "Carl grabbed a stump. It broke at an angle. He almost fell again. He yelled some stuff I won't repeat. The guys started laughing harder than before." "I bet he got real mad after that." I said. "He was until he saw, we all saw, that it wasn't a stump. It was an arm, frozen solid." "An arm? A people arm?" I said. Eyes widening. "Yep. A frozen arm buried in the ice and snow. It reached straight up." He moved his own hand toward the ceiling. I watched it. "Hand as black as coal. Frostbite. One of ours from another unit. No telling how long he'd been there. We chipped him out, tied him to the back of the tank, and put a blanket on him. The guys got quiet. We left his broken arm…you know…sticking up. Didn't want to break it all to hell even more than what Carl did to get it under the blanket." "He was frozen sol…. solid?" I said. "Yep, solid as a popsicle. Keats, Wallace A. on the dog tags. Always remember that name. Thought you were old enough to hear that story. It's kinda cold today, but it ain't real cold. You follow?" I shook my head, indicating I followed. A brief image of a man's frozen arm, black hand sticking out of a blanket as it rode the back of a tank crunching snow in a frozen wasteland, popped in my head. I changed the subject. "That's really cold, but in the pictures, you're not even wearing a jacket?" I said, thinking of a manila envelope of black and white photos in a footlocker under his bed. I stumbled upon it one summer playing hide and seek. His scrawled handwriting on the backs of them giving the name, date, and place. Wilbur, Otis, Robert, Earl, Harry. Names you don't see anymore, replaced with Hunter, Jordan, and Brandon's. Soldiers younger than my two sons now. Some labeled "KIA" or "MIA." Through the years, if something triggered a memory, he would summon a story about them, each with a "that son-of-a-buck" in it somewhere. Odd, quirky stories about young men with nowhere else to turn but to each other. "Those are summer pictures." He said. "That track came off in the winter. Korean winter. It gets to zero here sometimes. It got to minus twenty, thirty, even forty in the shade over there. Cold enough to freeze a man solid in no time." He held the coffee cup with both hands and took a long draw, remembering a frozen soldier across time and the Atlantic Ocean. "GI stuff wasn't made for that kind of Siberian cold." He said. "What's Siberian cold?" I asked. "Look it up in the book." He said. He had gotten me a big encyclopedia called the Volume Library when I was eleven. He said it would be good for school. Three inches thick. Twenty-six hundred pages. Pre-computer Google. I wrote a hundred book reports pulling from that literary anvil. Still have it. "OK. I will." I said. "Is that where Siberian Tigers live?" He ignored that question, as if he wasn't sure himself, for something relevant. "You know the most important thing I had over there?" He said, pausing to light a cigarette. I leaned forward, eyes wider than before, waiting for a story about guns, tanks, bayonets, hand grenades, all things combat. Naïve candy to young boys. A taste not fully squelched by the story of a frozen soldier and a black hand of death. John Wayne and the U.S.A., parades, medals, and shiny boots. The Green Berets. The Dirty Dozen. Kelly's Heroes. "Socks. Dry socks." He said. "Socks?" I said. "Yep." He turned his head to blow smoke. From the couch, Timothy yelled something nonsensical in his sleep. He did that a lot back then. It sounded like Truck Truck Fire Truck. I wasn't sure then if it was Truck Truck Fire Truck. I am now. That's another story. Timothy mumbled something after that, nowhere near words. I giggled. He grinned behind a haze of smoke and continued. "Those GI boots - we called 'em Mickey Mouse Boots - had thick fur lining. Make your feet sweat. Had to keep your feet dry, or you got frostbite. Lose toes, maybe a foot. You get frostbite, you were done. That would get you home, and I think some thought it was fair trade, but most guys wanted to come home with what they left with. Extra pair of dry socks tucked away was like a biscuit-smelling hug from your mama." He winked at me. "Did you fix it?" I said. "Fix what?" "The track, the broken tank thing. How'd you fix it if your wrench broke?" "We had others. You can fix most broken things, just need a little know-how and patience. You can fix most anything but a frozen arm." He said, peering over my head to the rain beyond the window. Thinking back on fixing tanks in the Korean winter with North Koreans and Chinese all around, a frozen man's arm sticking up next to you, I suppose the busted pocket knife wasn't daunting, though I worried he would cut himself. I worried all the time. I worried he would fall in the bathtub, hit his head, break a hip, and lay in pain for hours. I worried he would die in his sleep, no one around. No matter how many times I offered to live with us, he declined. His second wife of twenty-three years was in a nursing home thirty miles away, almost all her seeds on the edge of the universe. Shady Acres, I think. I have a hard time remembering the name of it. They all sound the same. Shady Acres, Magnolia Village. Heaven's House. Shit like that. I was working to get him there. I took him in June to see her. She perked up when she saw him, as much as a ninety-year-old woman can. She lay in bed on one side of a room lit only by gold sunlight making its way through the half-open blinds. They held hands like teenagers. "I love you." He said. "I love you too." She said. They talked for a while. I tried not to eavesdrop. It ended with something about her sister and a red sweater she needed from her closet. "When are you coming home?" he asked her. "I'm sure I'll be home soon." She said, her voice papery thin as if transmitted through a rice paper phonograph. Then she called him by her first husband's name and said we need to get the room ready for the baby. I pretended I didn't hear it. "Love you." He said as he kissed her on the forehead, then turned to me. "Ready to go." I kissed her on the cheek, and we left the room. The whole place smelled like ointments and black-eyed peas. A few residents sat in wheelchairs, grouped together at odd angles in the corridor like wayward shopping carts in a parking lot. Two peered at me, head bobbing, eyes vacant, no seeds. A white man with a black knit cap, mouth open, revealing a toothless maw. A white woman, staring straight through me to the playground she danced on as a child when Roosevelt was President. In a nook out of the way of traffic and the over-lit corridor sat a coal-dark man. His face reminded me of a blues album cover I had. Mississippi Delta Blues guy named "Blind Willie Walker" staring up from a dive bar piano. Blind Willie had clear, dark brown eyes. They caught and held mine. I nodded. He nodded back. Our three-second eye-to-eye told me he had seeds left. It also told me he knew what my dad did not - this was not a hospital; his wife would not be coming home as soon as she got better, and the place DID smell like ointment and black-eyed peas. Driving back, my dad stared out the window and said, "I'll be glad when they let her out of there." "Me too," I said. We waited for a room to open up at Shady Acres. One always did. It is the nature of the business. A home health service stopped by daily to check on him, at least that's what I paid for, but I wasn't sure they kept that schedule. I wondered if he even noticed. I wondered what he did when he couldn't sleep. Wander the dim rooms wondering where his wife had gone, thinking she had left him? Sit at the same kitchen table at 2 AM, drinking coffee, smoking a cigarette in the dark? The kitchen was desert quiet that Wednesday afternoon. I could hear my breathing while he moved the knife pieces around on the placemat with thin, arthritic fingers. His face gaunt, thin neck. The khakis and short-sleeve shirt wrapped him like a tarp. I thought about helping but didn't, thinking the task was good for his mind. Besides, the sun seemed closer than it should have been, reflecting off everything outside and focused by a thousand lenses on me. I rubbed my eyes, squinting, reminding of a headache I had tried to ignore. In the distance, someone was mowing the grass. "You ok. How you feeling?" I said, "Need anything?" "I'm good. Feel fine." He said. His usual response. He got up to go to the bathroom. "Too much coffee." He said. Once out of sight, I opened his wallet. It lay on the table near the keys to his '87 Lincoln Town Car that didn't start (I had removed the battery months before). No cash. Not a single George Washington. His driver's license expired in the past October. I could see the man I remembered in that license photo, still visible, looking back at me better than the live version in the bathroom. A condensed version of his face held together in that little square maintained a man that used to be. The one that took me fishing and hauled me and my brother all over country roads in one of his old beaters to just take a drive or visit friends and family. Sit on a porch. Drink a Double Cola in one of those red labeled sixteen-ounce spiral bottles. Tell a story about some son-of-a-buck. I pulled three crisp twenties out of my wallet and put the money in his worn brown bifold. His money anyway. I managed his checking account as I worked to get him in the nursing home. Three twenties were enough. I was coming once a week, but a man needs folding money and a pocket knife on him at all times. He told me that one summer when I was still very far from being one. He splayed the bills of his cashed army pension check in his hand like a millionaire. Something like $450 dollars back then. He grabbed five one-dollar bills, folded them three times, and handed it to me with a sly smile. Foldin' money, he said. Don't tell your little brother. Five dollars in the mid-70s for a kid was some pretty serious green. He sometimes walked the half mile into town along city streets to the last Demby's Restaurant in the United States. It was a dirty, beat-down burger joint that used to be a sizable chain in the south. This last one hanging on independent. I heard a guy in Florida kept it just to have the property locked up. Lunch tasted like breakfast. They never cleaned the griddle. Old timers, check-to-checkers, and teenagers are the primary patrons. The old guys sat around small square tables in the middle of the dining area, surrounded by booths that lined the walls. Chairs mismatched and sticky. Every table requiring a folded napkin under a leg to keep it from tilting like the Titanic. The old men drank coffee and pontificated about things old men pontificate about. Two months before that Wednesday in the kitchen, he wasn't home. I found him at Demby's, sitting with two other men whose tread had seen better days. He looked at me as I walked up like a stranger. I worried the day had come when he wouldn't know me when a face that looked identical to his didn't register. I prepared to say Hey Dad, help him out, save my heart. "What's going on?" He said. Before I could the Hey Dad out, he saved me. "This is my boy." He said. A tear welled up in my right eye. I held it off and wiped it away, feigning a stuck eyelash. It's odd to be called a boy at Fifty-Two, but when your dad says it, every son is a kid again. Not the son worrying about work, bills, and nursing home placement, but the son who grasps his father's hip in a Mississippi state park or lays his head on a smoky, Old Spice smelling shoulder as he's carried off to bed. The son that would trade a stack of folding money a mile high for the way he told those geezers This is my boy. The two old men nodded. "Nice to meet you," I said. They stared at me like it was my turn to do a card trick. "I'm getting lunch. You need anything?" I notice his coffee was half gone, just two bites out of his small cheeseburger. "No, I'm pretty full." He said. I remembered when he would devour ten White Castle cheeseburgers-he called them sliders- from those little square boxes while making faces at me and Timothy. He chewed and hammed it up like it was the best food ever created while rubbing his hand over a protruding belly that had disappeared fifteen years ago. At the counter, a very thin young girl with a nose ring asked me. "That your dad? The one in the blue striped shirt?" I looked at the menu. Faded pictures of hamburgers, hot dogs, and chicken. All the same color, even the lettuce, ketchup, and mustard. A grayish brown. The last Demby's in America didn't give a shit. "Yep. That's him." She leaned toward me, smelling like biscuits and some kind of meat. "He didn't have money. I told him don't worry about it, just bring it in next time. He's in here a lot. Tells funny stories." "Yeah. He sure does. I got it." I ordered the No. 1 combo, no pickle then paid up. A dollar eighty-six. The last meal I ever bought him. "We'll call your number when it's ready, sixty-seven." She handed me the ticket. I sat at a small two-seat table next to theirs and listened to them carry on about people I didn't know and things before my time until I heard "Sixty-Seven." The No.1 cheeseburger combo tasted like the No. 1 breakfast burrito combo. He told them the story about how I got lost with a black boy when I was five. I had heard it a million times. Those early days when Mom's hair hadn't started turning gray, and the four of us were together while he was stationed in Heidelberg, Germany. "His mother called me, crying and hysterical." He said. "We looked around for hours at the apartment complex, then we called the German Police." The old men looked at me. I felt oddly embarrassed to have caused such a fuss. "The German police found them. Middle of a coal yard, train tracks all around. Playing with a football." He sipped his coffee. "Filthy. Head to toe. If it weren't for the hair, we wouldn't have known which was which." He said, chuckling. Only the younger old man let out a grunted laugh. The oldest man furrowed his brow, confused by a subtle punch line. He always told the lost son, coal yard, train track story. It was his go-to. Through the years, he changed it up a little, as if bored with it. That last year, no two words were different, as if he couldn't create on the fly anymore, his most impressive storytelling gift, floating way. Jazz to sheet music. Suicide knob to ten and two. Dandelion seeds in the breeze. After eating, I told him I needed to go but would come back soon. He said OK. I wanted to hug him but didn't. Men. We have issues with public displays of affection. Doesn't bother me now. Sitting in my car in that crumbed asphalt parking lot littered with cigarette butts, straws, and food wrappers, I watched him through the hazy, dusty window of the last Demby's in America. He gestured to his two-man audience, hand up, head cocked, periodic grin. Slower, but the same. He was in his element, telling stories to old men that knew what a Studebaker was, that "sparking" meant dating, that a sawbuck was ten dollars and that Co-Cola was the only way to say Coke. The bathroom door opened. I put his wallet back on the table where he left it amid a scattering of junk mail, unpaid bills, several coins, a glass ashtray, and half a pack of generic cigarettes. He came back to his chair and sat down with an exhale through closed lips that made his lips vibrate a little like a horse. He looked six months older than the version at Demby's only two months prior. "Your brother in the car?" he asked. I dreaded any question about Timothy, killed in a wreck over ten years before at an intersection by a drunk driver. The impact was minor, but his truck burst into flames. For reasons we will never know, he couldn't get out. I have nightmares about it. You could call it my go-to nightmare, a little like the lost son, coal yard, train track story, only mine has never changed. I am on a sidewalk, unable to move, frozen, my arm over my head, my hand black as night, frostbite, holding a Kodak 110 Instamatic. My little brother, forty years old, staring at me in panic, his face pleading with me to save him as it is engulfed into red flame. Over the roar of the blaze, he is screaming Truck Truck Fire Truck. For the last year, he forgot about Timothy. I had no heart to break that news twice, so I responded the same way. "No. He's on vacation, remember?" I could see his subconscious grasping at an escaping seed, missing the one with his dead son's name on it and a picture of a mangled inferno of a Ford F-150. I braced for his response. "I remember." He said. "You want to get some lunch?" I said. "No, I'm o.k." He picked up pieces of the knife again. "Need to fix it." He said. "When was the last time you ate?" "I had something this morning." I knew he probably didn't, and he probably didn't remember if he did. It was something you said when your son asked the question. When I left that day, I gave him a hug as he sat there. "I love you." I said. "I love you too, son." He said. "When Timothy's back, maybe we can go fishing." "That would be great." I stood at the back door. "I'll be here Saturday. If you need anything, call me, ok?" "I will. Love you, son. Be careful." I stepped to the covered porch, then watched him through the window. He moved the knife parts around. Leaving him at that table in a house that must seem like a public library to him in the night's quiet, when all you hear is the ticking of the grandfather clock in the living room and the rattle of your own tired breathing, made me feel like the worst son I could be. That was the last time I saw him alive. Friday morning at work, 10:27 AM, I got a call on my cell from the city police. Almost didn't answer it. Unfamiliar number. Of all the words sent my way on that call, I registered five - we found your father deceased. A female officer told me some other things I don't recall. Only those five words mattered. My mind flashed images of him at Russell Creek, baiting my hook, wading out into the deep water for a swim with Timothy giggling uncontrollably on his shoulders, sleeping on the couch on his side, arm extended, parallel to the floor, riding in some old car, ashes from a cigarette or Swisher Sweet cigar littering a polyester shirt. A thousand images, from the oochie park to him at the kitchen table, working on a busted pocket knife. I could have taken the parkway, but I took the back roads. He took his sons on those back roads during those Summers with your Father. I did the same with my two boys and do the same thing when I am alone. There's something soothing in the roll of the paved ribbon through the southern countryside, the alternating sun and shade, the things you see around every curve, over every hill, some expected and some not. That day was different. I drove in a trance, mad the sun shined when it should not, mad the rains from the last two days had cleared the way for a pristine blue sky, upset the weather was warm, humidity low. A perfect day. It wasn't right. Pelting rain, dark clouds, bullish wind, and bending trees churned inside me. I identified him at the morgue within an hour after getting the call. Entering the back door as instructed, I descended two flights of steps into the basement of an old utilitarian brick building. The basement greeted me with hard checkerboard black and white tile, bare walls, hard walls, harsh lights, and somber gray and beige colors. I looked for Room B10. A thin, shorter man approached from the other end of the hall wearing black pleated pants, a narrow belt, and a white short-sleeve shirt. Old style, I thought. He stared me down all the way, never changing expression. I assumed he came to collect me, take me to Room B10. As we passed, he gave a slight smile, but never stopped. I took two steps and turned around. "Excuse me, can you point me to B10, am I…". He was gone. It was a long hallway. I only took two steps. His back should have been ten feet away. I listened for footfalls up the stairs, voices in a side room, something, anything moving. Nothing. I found Room B10 at the very end of the next hall to the right. I took a breath and opened the door into a cold, large room with florescent lighting that made everything too clear - good for the staff, not good for the visitors. After a brief introduction and condolences, a very tall man of maybe forty, wearing blue jeans and a golf shirt, turned to a table behind him and removed a white sheet from a prone body, the only one in the room. "That your father?" he said. I took a glance toward the steel table three feet in front of me. I didn't need my eyes to confirm what I could feel. It was him, and he was gone. I didn't need to see the feet once in heavy combat boots in frozen snow, now covered in the small familiar brown shoes, the left one with a broken shoestring tied into a knot, hanging to the side. I didn't need to see the motionless line of his leg to the crook of his right wrist broken in a jeep accident while stationed in the Philippines. I didn't need to see the angled plane of the side of his face and a nose that I have, or the wisps of gray hair like baby bird feathers moving from the push of air conditioning above the table. "Yes." I said, trying to keep my composure, failing to contain the younger son in me seeping out of every opening in my clothes, tears forming in the corners of my eyes. "We found him at the Cemetery Park early this morning, in the back, the older part, feet on the ground, leaned over on the iron bench back near the tree line, like he was asleep. It rained pretty good here last night. His clothes got soaked. A lady putting flowers out found him this morning. Best we can tell, he got there yesterday evening near dark. You have family in that section?" The man said. "Not that I know of." I ran my hand across my running nose and then walked to the left side of the table, where I could see his face. Along with kissing my mother's forehead for the last time, it was the hardest few steps I have ever taken. I don't wish to take any more for anyone I love. His face was cold to the touch, his right eye partially open. "I'm sorry Daddy." I said, running the fingers of my right hand through his hair as I grabbed his lifeless right hand with my left. My tears came without embarrassment, and I regretted a lost hug at the Last Demby's in America and all the lost hugs and I love yous lost over so many years. The tall man stepped back to give me privacy. A few seconds later, he broke the silence. "I know old people stay cold and all but a heavy coat and corduroy pants. It was already in the eighties this morning." He raised his eyebrows. I almost punched him. He saw my eyes flash. "I'm sorry. That was uncalled for." He said. "The only thing we removed, and only because it was falling out when he moved him, was this." The tall man turned to an adjacent table and picked up a damp pillowcase, half full of something pushing the sides out. I paid no attention to it before. He handed it to me. "No disrespect, but was your dad… you know… all there, so to speak?" "Mostly," I said. I opened the wet bag, then hitched a deep breath. My lips trembled. Tears came more than ever, running down my cheek into unshaven stubble. Inside the pillowcase were six pairs of thick wool socks, rolled up like grapefruits. One pair white, one black, obviously old. The other four pairs newer, identical hunter green, bought in a pack from a store I knew to be closed over five years ago. "Do you know what those are all about?" he said, curiosity getting the best of him. I grunted a combination of a laugh and a cry. "Sometimes life gets too cold. Colder than you can take anymore." I said. The tall man said some things. I don't recall any of it. Four days later, we had a brief service and buried my father in the small cemetery of his hometown. He wore a blue suit and gold tie. I bought it special. I am almost positive it was the most expensive thing he had ever worn. I tucked the pillowcase of socks past the small dividing curtain that separates the top half of the coffin from the bottom next to his right leg, the one Timothy clung to for that picture at the oochie park. I read a eulogy, choked up on every line. After the service, alone with him in that room of folding chairs and white columns, I leaned in. "You'll never be cold again." I put the park picture and the mystery photo in the breast pocket of that blue suit. I kissed him on the forehead and walked away to lead the small procession to the burial at the cemetery. The perfect day from five days before was less perfect, much warmer. Clouds threatened rain in the west. Under the green funeral canopy, I listened as a bugle played Taps, and the twenty-one gun salute cracked loud shots that made a little girl - I think my first cousin's granddaughter - grasped her ears. I thought it a blessing his wife at Shady Acres had no idea he was gone. I watched the white-gloved old men from the honor guard stoop to the ground to collect the casings, then count them before handing them to me in a cloth drawstring bag. A preacher said the usual pablum about eternal life and no more struggles. It rang hollow. They lowered him into the ground near the fence under a towering oak tree in that small private cemetery on the top of that hill by the Methodist church, a half mile from where he was born in a farmhouse just before the Great Depression. He would lay feet from his father, mother, and grandparents. I stared at the headstone he bought fifteen years before, the "Died" date freshly chiseled. That was three weeks ago. Last night, I was near sleep in my recliner when that new thing that won't wipe away - that new coffee ring on some table in some corner of my brain flashed like a photo from one of my shoe boxes-the man from the morgue hallway. The man with the lingering stare and the older clothes. He drifted to my sleepy consciousness and sat there waiting. I went to my office, opened a file cabinet. Lost in the back, behind the files for home insurance and appliance warranties, was a manilla envelope. I dumped the contents on my desk. Items my aunt had given me ten years ago, a year before she died. A scattered mound of newspaper clippings, family members' births, marriages, and deaths, family tree diagrams, and old photographs of men and women from long ago. The men somber. The women wearing broaches and plain faces. "You're the only one that will take care of this." She said. "Some things there that might interest you." I had only given it a quick glance then and forgot about it. I went through everything again. Some things familiar, some things not. The nagging feeling of something left undone remained. Disappointed, I picked up the envelope to put the material back in when my fingers discerned the bottom was thicker than it should be. Looking inside, another envelope, the smaller type with the single top flap, was stuck in the bottom corner. It took a pull to get it out. I opened it to find a small newspaper clipping with a paper clip holding a folded note, written in that bygone handwriting style. The blue faded ink written by my dad's mother whom I was told was a hard woman. It read: James killed and robbed. May 13, 1935. The only thing left his pocket knife. Will give to Reuben when he is older. Next to the folded newspaper clipping, a wrapped note from my aunt, in her familiar printed style, paper clipped to a black-and-white picture of a man in a white short sleeve shirt, black pleated plants, and thin belt, standing in a yard, his face turned, looking down to a small barefoot boy squatting in the grass, looking back up at him. In the background the corner of a barn. The note read: Copy, original lost, J. R. Cobb (Daddy) with Reuben, six years old, home place, Milltown, 1933 I reeled, took a breath, and shook my head. The man in the picture passed me in the hall at the morgue. I've been through this a thousand times. I'm not crazy. Our faces were two feet away. It was him. I went to my father's memory box. I took the two copies I made of the originals that now rested with my father in a coat pocket under that oak tree. I placed my copy of that second picture side by side to the older copy. No mistake. I sat back in my chair with such force it almost toppled over. The same. The second picture, the man obscured by the colors from the oochie park photo, was my grandfather, my father's father. He passed me in that hallway. I swear. I have studied that photograph against that memory, a memory that has stuck like a ring on a table a thousand times. It was him. It made sense to me. My father, with enough seeds left to know his time was near, urgently trying to repair a knife with fused jointed fingers and opaque eyes so he could hand it to his father on the other side, wherever that is. In the end, unable to fix it, he put the pieces in his pocket and carried on like a good soldier. The bench in that hidden cemetery corner under those big oaks where the squirrels run trumped being slumped over a kitchen table or laying on a linoleum floor. He had enough seeds left to keep some dignity. I think about his last days often. That's natural, but also because I am on the first steps of my own to some park bench in the rain. Three weeks ago, I stared at a calculation. The numbers, lines, and symbols looked like Hebrew text, just for a second or two, but they did. Not a big deal, you might think, math's not for everyone, but I am an engineer. It is my second language. Yesterday, I forgot my middle name. Just for an instant, but I did. That is one strange feeling. Worse than the math. You don't use it, you lose it can be rationalized for math, not your middle name. I suppose those may be the first two dandelion seeds of mine to meet the wind. I keep a pillowcase stuffed with four pairs of extra thick socks in a foot-locker in my office. In that locker is an "In Case of My Death" manilla envelope with burial instructions - songs to play, poems to read, who'll carry me off. The usual stuff. My wife knows about the envelope, not the pillowcase. The last instruction on the list is to make sure that pillowcase is buried with me. They will think I died crazy, but I don't mind. It's an inside joke. I hope I have many years of good life left, but you never know. Life is a strange long hallway in a basement with many doors. Things happen you could never predict or understand. Frostbite and burning trucks. I fixed that yellow pocket knife Daddy. It took a little patience, but I got it back together solid and cleaned it up nice. Looks almost brand new. Blades sharp. I carry it with me. It cuts the ribbons to a thousand memories that make me smile when I need it, when I can't remember my middle name or how old my sons are. I lost some opportunities while you were here, so here is a start to get them on the record. Thank you for the shoulder carries to bed, the birthday cards with cash you couldn't spare. Thank you for serving your country in a cold hell on a foreign land. Thank you for the hugs and the times when you got tough. Thank you for the car rides to nowhere, in particular, the Double Cola's in those tall spiral bottles on those dusty roadside country store porches that are long gone. Thank you for the county fairs and the quiet nights watching Gunsmoke on a black-and-white TV. Thank you for teaching me things that three-inch book could never do. Thank you for the stories. So many stories. They are part of me, their seeds deeper and tighter than the gusting winds of disease can rip away. You don't need those socks where you are, but I'm bringing you some extras anyway when the time comes. I'll bring that little yellow knife, and you can show your dad that you took care of it. The four of us will get back to that oochie park, take a new picture, side by side. Hell, maybe Blind Willie Walker can play us a blues tune, and twenty-year-old Wallace Keats can keep rhythm with a couple of sticks, and thank you for getting him out of that ice and out of the cold. Maybe that big man is there. He can snap that photo again, and this time, the colors will never bleed. I love you Reuben Walter Cobb, you ole Son-of-a-Buck. |

|

|

|